Ever wondered about or wanted to pursue scientific research in a provincial park? Today’s post from Northwest Zone Ecologist Intern Lindsey Boyd and Northwest Senior Assistant Zone Ecologist Evan McCaul should answer your questions.

Spread throughout Ontario, our 340 provincial parks protect 8.27 million hectares of land and 1.3 million hectares of lakes and rivers. There are also 295 conservation reserves that form a protected areas network along with parks. From mosses to moose, protected areas provide endless research topics and opportunities.

Scientifically speaking, protected areas are an excellent place to conduct research. They can be used as a reference site to measure natural conditions within a broader landscape study, or provide an excellent place to study climate effects on species and systems in a place with fewer human pressures like roads or high levels of noise, light, and air pollution.

So you want to do research in a provincial park?

First off, welcome!

We’re happy to have you join our growing network between parks and external researchers. But before you grab your dragonfly net and chest-waders, there are a few things that you need to do first.

In order to conduct research in a provincial park (or any protected area in Ontario), you need to complete the Research Authorization Process. This helps us to ensure that no undue harm will come to the precious natural and cultural resources that our parks protect. This also allows us to connect with you and formalize an information-sharing agreement.

Applications to conduct research in a protected area can be submitted online here.

Once received, Ontario Parks and Protected Areas staff will review your application. Research terms will be agreed upon by the applicant and staff, an authorization letter will be sent to the principal investigator, and research can begin.

We are in the process of streamlining this approach, but it currently takes up to 60 days to complete the approval process. As many of us were and are researchers ourselves, we understand that there are many logistical hurdles to planning field season research, but the sooner you get the approval process going, the better it is for everyone involved!

Once the researcher’s field season is complete, reporting begins.

Data and a report must be submitted. For multi-year projects, any proposed changes to research activities for the next season must be noted.

The data and results in these reports are extremely valuable to parks, as we can use it to better protect and manage our resources. Ontario boasts a huge and unique landscape, so cooperation in research is necessary to gain the best possible understanding of our landscape and species.

Want to align your research with the needs of our provincial parks? Check out our Top 10 Research Needs!

For more information about whether you require authorization for your research and how to acquire approval, check here.

A brief history of in-park research

To the best of our knowledge, the earliest record of research in a park dates all the way back to the 1930s, when Lake Trout were studied in Algonquin’s Lake Opeongo. Research activities in parks took off in the 1970s, likely due to the popularity of the environmental movement and expansion of the Ontario Parks system allowing extra funding and grants for research.

The importance of research in parks is now clearly recognized by legislation, where one of the main objectives of Ontario Parks as set by the Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act (2006) is: “to facilitate scientific research and to provide points of reference to support the monitoring of ecological change on the broader landscape.”

Over the last 10 years, approved research activities in the province have increased just over 140%. It should be noted though, that some of this increase could be attributed to an increase in use of the permitting process.

All scientific research done by internal Ministry staff and external researchers is incredibly valuable for enabling park staff to make science-based management decisions.

Riveting raptor research: Project Peregrine

An example of ongoing research in Ontario Parks involves the study of Peregrine Falcons. Occurring in Northern Ontario, Project Peregrine has been coordinated by the Thunder Bay Field Naturalists since 1989. The primary goal of this work is to monitor Peregrine Falcon populations within the Lake Superior Basin.

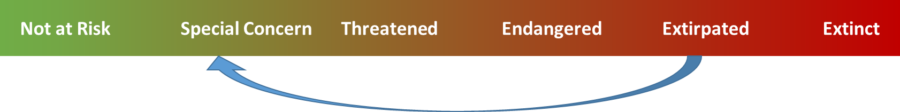

This research is particularly important because Peregrine Falcons were extirpated from this region in the 1960s due to exposure to the pesticide DDT causing a population collapse. Extirpated status is given to species that are no longer present in an area that they previously inhabited.

Between 1989 and 1996, 87 young peregrines were placed in hack boxes and released into their cliff habitat. From 1996 to present day, these falcons and their young have been closely monitored.

Monitoring these birds is not an easy task, because they prefer to nest on steep cliff faces. Each year, peregrine nesting sites are surveyed utilizing helicopters. Expert climbers repel down cliffs to collect new chicks that are banded and assessed.

As of 2017, there have been 27 occupied territories identified within 11 provincial parks in northwestern Ontario. This provides an opportunity for park staff to assist in this research and learn from experts about how to protect these birds and their habitat.

The good news is that the peregrine population has been slowly recovering!

Each year, more is learned about peregrine territories and breeding pairs of birds within this population. Project coordinator Brian Ratcliff reports that since this project began, over 600 peregrine chicks have been banded.

Learn more about Project Peregrine here.

As of 2011, Peregrine falcons have been up-listed to a species of Special Concern status in Ontario. This is just one of many examples of how research in Ontario Parks is very valuable and very cool!