Today’s post comes from Mat St-Jules, a park interpreter at Samuel de Champlain Provincial Park.

The sights of the Mattawa River keep drawing me back.

I find incredible beauty in a scraggly cedar clinging to sheer rock or in the gleaming coat of a river otter standing on a sandbar. But, of course, these marvels don’t stand on their own.

Below the wildlife and past the trees is the foundation of this land: the geology it all rests on.

The bedrock at our feet

The course of the Mattawa River tumbles across the Canadian Shield. Near the beginning of its path, it widens to form Turtle Lake. Dotted with rocky islands, it’s typical of a lake in this region.

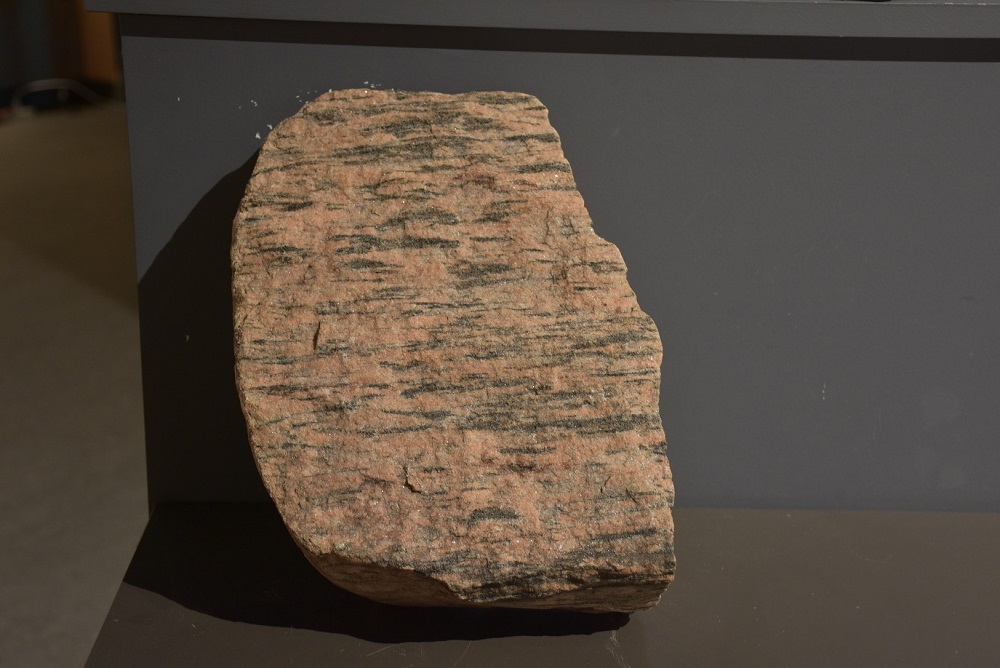

The stone here is mostly gneiss (pronounced like “nice”), a pink rock with streaks of black. It’s a metamorphic rock, meaning it was created from a previously existing rock that was transformed with incredible heat or pressure.

In this case, the pressure came from the collision of continents roughly 1.2 billion years ago. That’s five times older than even the earliest of dinosaurs, before the evolution of fish, and before the evolution of insects.

This collision folded, cracked, and thickened pre-existing rocks, forming a new mountain chain jutting tens of kilometres into the sky. This time was known as the Grenville Orogeny (orogeny being geologist speak for mountain-making).

Over the eons since, the Grenville Mountains have been eroded away.

The gneiss formed below these peaks is known as Grenville Gneiss.

Its dark and pale banding is caused by minerals like micas that have aligned and organized themselves against the pressure. Some of the rock material reached such temperatures that it melted and flowed through the surrounding stone, eventually cooling into swaths of granite.

Rock torn apart

Those continents that collided eventually separated again 200 million years ago.

The Mattawa River follows along one of the faults that developed during this time. A fault is a fracture in the Earth’s crust. This one is appropriately named the Mattawa Fault.

Striking evidence of its existence can be seen a little way down the river at Talon Chutes.

Here, the current runs down a narrow gorge flanked with cliffs extending far above the water and echoing the sound of the falls. Along the lower half of the Mattawa River, similar cliffs are frequent sights.

The Mattawa Fault is not the only one in the region. In fact, it is the most northern fault in a whole fault system.

Together, they form a structure called the Ottawa-Bonnechere Graben. “Graben” may be a new word for most of us, but think of it kind of like a valley.

Because of the separation and stretching of the continent, the Earth’s crust shifted downwards. This happened along the length of what would be a valley. The Mattawa River and its fault is a section of the larger and more complex graben.

Geology in action

Geological forces have not stopped shaping the Mattawa River. The slow erosion of the surrounding hills is probably most noticeable at their base.

Here, small streams run into the Mattawa River. These have picked up sediments, created erosion, and then drop them as sandbars and sand deltas in the main Mattawa River valley.

There are such sandbars near Samuel de Champlain Provincial Park at Elm Point, Purdy Creek, and Simpson’s Falls.

The sandy shoals make these areas ideal spots for a rest-stop during a day of paddling. Visiting these lovely beaches puts you face to face with the continuing impact of geology on the landscape of the Mattawa River.

The scenery of the Mattawa River is built on its geology

Paddling down its length makes me realize how much our world is shaped by these powerful yet invisible forces.

It’s a fact I often forget, but the Mattawa serves as a stunning reminder.

And, for that, I am thankful.