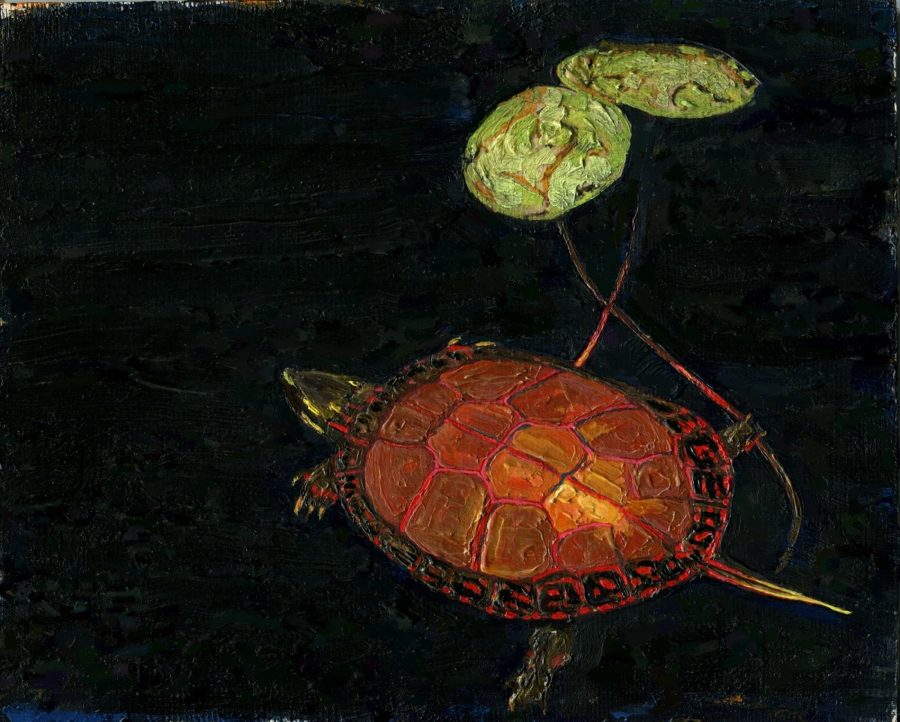

Today is dedicated to telling the story of Painted Turtle #353: “Martyn of the Madawaska” (mostly true, with some creative freedom by the author).

He is not particularly unusual for a turtle but, like most, he has an interesting story that begs to be told.

Part 1: The beginning

The year was 1984. It had been nearly a century since the first trains rattled past Wolf Howl Pond (illustrated below) and a few decades since the last railway ties had been pulled-up.

Now, the embankment at Wolf Howl Pond was a popular hiking trail in Algonquin Provincial Park, famed for its wildlife viewing, and one of many sites of turtle research in the park.

Hikers, however, were not the only ones to make use of the sandy slope. The dog days of summer had passed.

As the weather began to cool, turtle eggs were hatching. “Martyn” the Midland Painted Turtle, later known as #353 to turtle researchers, would pip his egg and wait in his underground nest chamber until the opportune moment…

Part 2: The early years

It is no small feat for a hatchling turtle to survive past the first year (or second or third!). It was now 2002, a full 18-years since Martyn hatched.

He had defied odds, overcoming a less than 1% likelihood of surviving from egg to the two-decade mark.

Martyn now bore identifying code #353 on his shell, a marking to be carried throughout his life, thanks to those pesky turtle researchers at the Algonquin Wildlife Research Station.

During his youth, he became restless and moved from his natal water body (Wolf Howl Pond) to West Rose Lake, a few hundred metres east — equally picturesque, brimming with waterlilies and abundant in wildlife — but his new home would only do for a while longer.

Martyn lingered in West Rose Lake until 2008, at least, watching the seasons pass. He was a turtle of great ambition. After all, there were a lot more wetlands to explore. The waterlilies are always greener on the other side, no?

Martyn’s journey continued (south)eastbound, destined for “big water.” There it was. He had finally reached Source Lake (illustrated above)

Part 3: Big water

It was in the big water of Source Lake that turtle researchers from the Algonquin Wildlife Research Station finally lost track of Martyn, which was plenty fine with him. He wasted no time exploring all that the wide open lake had to offer.

Martyn bobbed along the surface, keeping careful distance from canoeists, just in case those researchers showed up again for his annual measurements and weigh-in.

Those motorized boats were something to be wary of too — awfully noisy, they were! Below the surface he met fishes and frogs far larger than he had ever seen in his old haunts.

Despite all that Source Lake promised there was one thing conspicuously absent: there were far fewer of his own kind.

Wolf Howl Pond and West Rose Lake were nearly brimming with Painted Turtles by comparison. It was not quite as homey, lacking the underwater jungle of waterlilies and sunlit basking platforms formed by downed lakeside trees. This place had a very different feel. It was not too long before Martyn felt a tug in the water, literally and figuratively.

He had found the drainage of Source Lake.

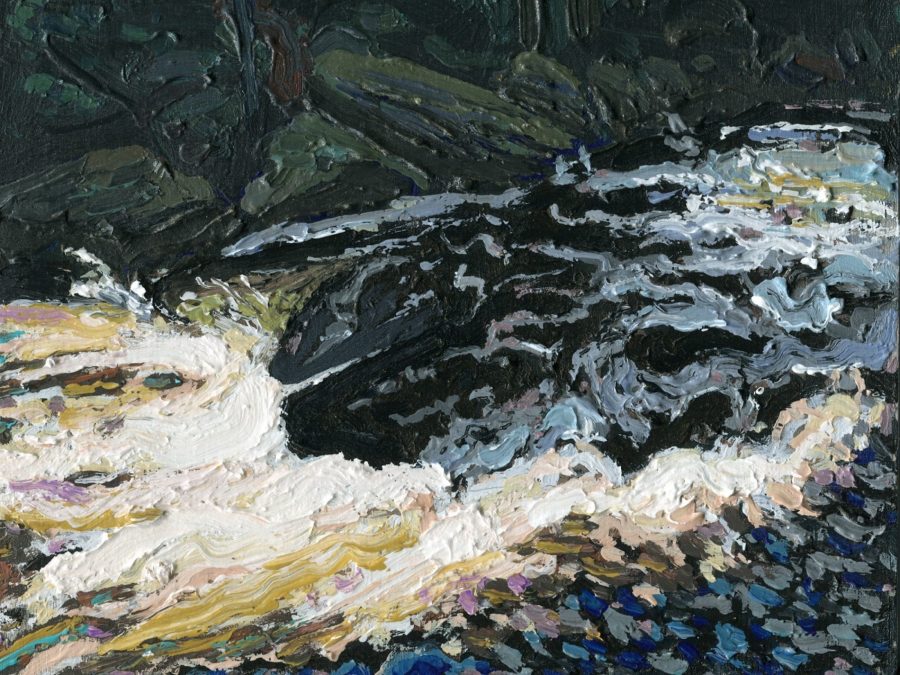

Onward to the whitewater of the Madawaska River? Dare he test the water? What lay downstream? There was only one way to find out…

Part 4: Into the uplands

A partial trip down the turbulent Madawaska River was not quite what “Martyn of the Madawaska” had in mind.

As it turned out, he was a turtle of still water.

Too determined (or was it too stubborn?) to turn back, the rest of Martyn’s trip downstream would have to be taken by land. In the water, he was in his element. Once submerged, his sleek shell, complemented by generously webbed digits, cut through the water with finesse.

On land, that same shell, a modification and fusion of the rib bones, was just plain cumbersome. Oh well, at least the shell served as a ready-made security blanket against most predators.

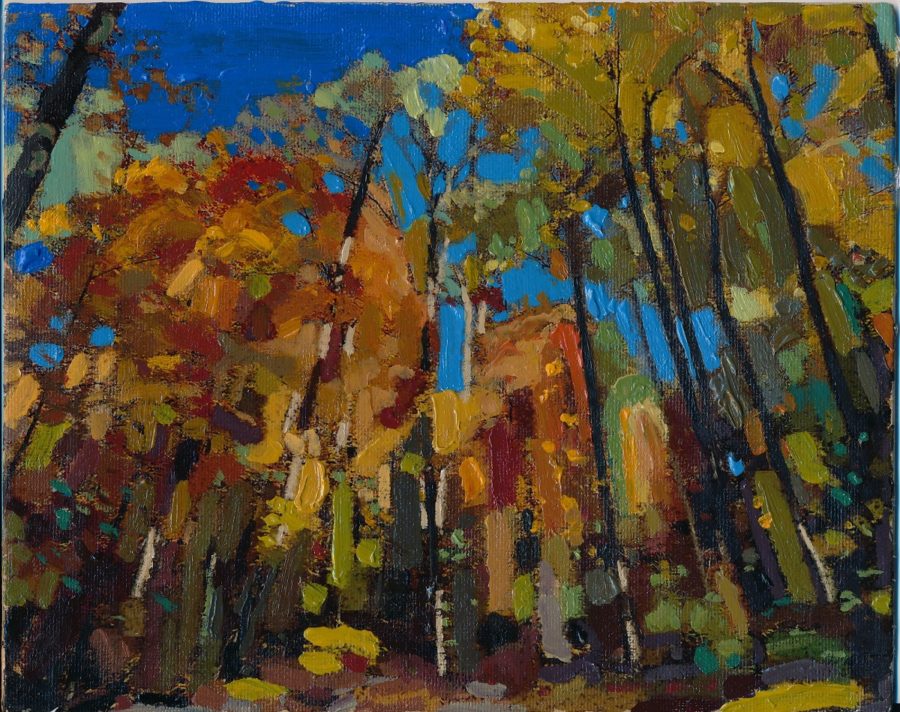

Martyn plodded alongside the river bank, slow and steady. Navigating the horizontal rotting trunks of many century-old maples made the forest an obstacle course. Supporting that heavy shell was downright hard work too so Martyn rested often and took these opportunities to look around.

Despite an existence so closely tied to an underwater world, his vision was adept at picking up colours, shadows and movements in the open air.

The full mid-summer canopy of the hardwood forest was a treat for the eyes, nothing like he had seen before, at least not from this perspective.

It felt like nearly a lifetime, which is a long time for a turtle, when Martyn finally made it to the edge of the forest…

Part 5: The hurry and the harm

Martyn sensed that the open water he so desired was close.

Now out of the forest, the openness that surrounded him gave a feeling of vulnerability. Despite clouds building in intensity on the horizon, he did not expect the rumble in the distance. The thundering soon came to him, and uncomfortably close at that.

The ground shook, rattling every bone in his hardened body.

The noise grew to a visceral roar as a flash of 18 wheels blew past. Martyn was nearly tossed backwards end-over-end from the incredible rush of wind and grit that pelted his shell.

What was that monster?

Martyn was on the shoulder of Highway 60, a high-volume provincial motorway cutting across the southern portion of his home.

He eyed up the blacktop. It looked impossibly wide, equal parts daunting and dangerous. Besides, his muscles already ached with exhaustion. It was now or never, and Martyn was not about to turn back to scramble over logs or attempt swimming up the swelled Madawaska River.

He had only hauled himself forward a few metres before another rumble began reverberating through his body. His acute eyesight focused on something shiny and approaching quickly.

Martyn’s immediate reaction was to brace deep inside his protective shell, which had served him well up to that point. Everything went dark.

Tires squealed.

A cloud of dust followed and there was a frantic thud as a car door slammed.

Before Martyn knew what was going on, he was hovering in the air and nearly on the opposite side of the asphalt, and in the direction he was originally heading. He remained tucked tightly in his shell and peed a little, out of fright.

Fortunately, this driver was “wildlife aware” — alert, astute and willing to help. Passersby stopped to see what all the roadside fuss was about. “No, no moose,” the helper explained, “but it is a turtle in need of help crossing the road.”

Martyn was one lucky turtle.

He had survived past the two-decade mark on his own. There would be at least another half-century ahead for him, so long as he managed to stay off roads.

With a gentle pat on the shell and accompanying well wishes (“keep off the road, little one”), Martyn was again left to his own devices, safe and sound for now.

He kept his eyes closed and did not budge for three quarters of an hour…

Part 6: Found Lake, found

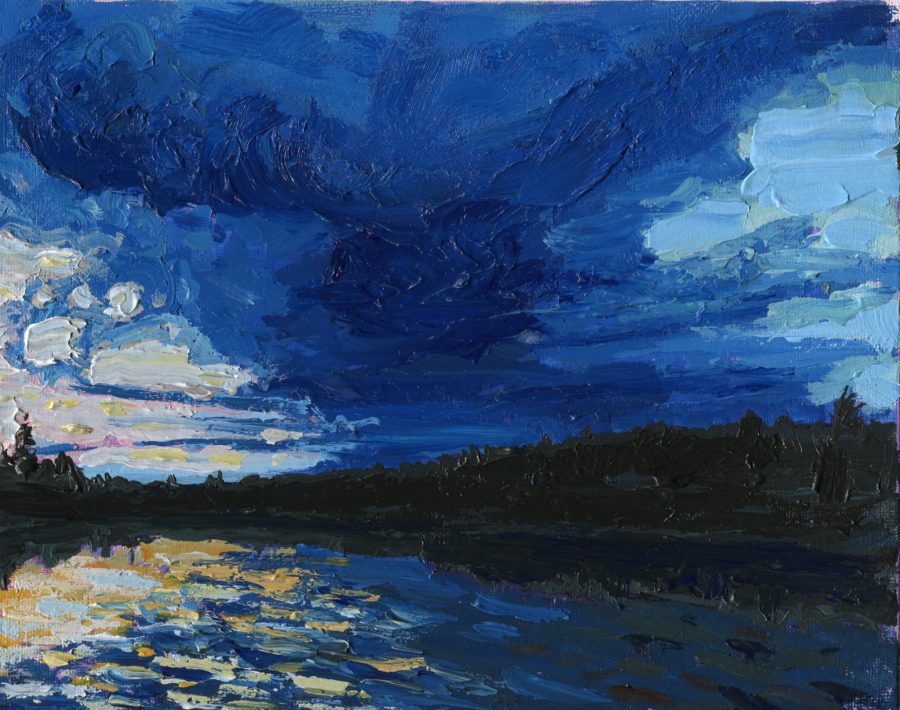

The air was cooling quickly and an early evening dew began condensing on Martyn’s shell. The road experience was downright jarring. It took nearly an hour before he worked up enough courage to extended his neck past the margins of his shell. Martyn simply blinked amid the fading daylight.

There it was: Found Lake, found.

Cast in this light the lake looked idyllic. The swaying pines, the wail of a loon, the open water and the buzzing mosquito: this was quintessential Algonquin.

Outstretched forelimbs offset his centre of gravity and he slid down the embankment toward the lake. He stopped ever so briefly to glimpse the horizon before slipping into the water and allowing his positive buoyancy to guide him.

The cool water refreshed his tired body and washed off accumulated dust from his land journey. As the crescent moon crept above the tree line and the Big Dipper took shape in the sky above, Maryn sought refuge under a submerged ancient log.

Tomorrow would be another day for exploring …

Part 7: Home…for now

Martyn seems to have settled into his new abode. Since 2012, he has been confirmed twice in the clear, cold, bottle-green water of Found Lake.

Martyn spends his summer days basking in the sunshine, foraging amongst the water lilies and occasionally going a short overland hikes. The rest of Martyn’s story is yet to be take shape and when it does, we will share.

Telling turtle tales

The story “Martyn of the Madawaksa” was inspired by Martyn himself (of course!), as well as the experience of naturalist Peter Mills, who found and reported the wayward Martyn in Found Lake in 2012.

This #ScienceStory was written by student researcher Patrick Moldowan and wonderfully illustrated by Peter Mills. Outside of some creative freedom by the author, this series is true to our research on Martyn.

As mentioned from the outset, Martyn is not a particularly unusual turtle. There are plenty of reasons to believe that his story is just as captivating as that of thousands of other turtles in Algonquin Provincial Park and beyond.

The nearly 75 years of ecological research at the Algonquin Wildlife Research Station has contributed significantly to our knowledge, policy, and conservation of species and ecosystems in Canada, turtles and their habitats included. These studies are made possible by donation.

If you’d like to support their wonderful work, visit the Algonquin Wildlife Research Station’s donation page or contact them at 705-633-5621 to learn how your donation will support research, education and conservation initiatives.