Today’s post was written by David Bree, Natural Heritage Education Leader at Presqu’ile Provincial Park.

It’s a blustery late-May day on Presqu’ile’s beach and a few birders are out watching the shorebirds. The birds wheel in and land for a few minutes of frantic feeding before lifting off again and heading out to disappear over Popham Bay.

One can’t help but be in awe of their flying skill and wonder. Where are they going? Where have they have come from? Questions no doubt asked by people since questions could be formed.

One may also ask, “where does the wind go?” since it seems impossible to track the wind and the birds that ride it. But, of course, we now do know where many of these birds go, thanks to bird banding.

The beginning of banding

Bird banding — the science of putting a numbered ring on a bird’s leg to identify it later — has been going on for a long time. There are records from the Middle Ages in Europe and China of banding falcons, mostly to identify them as someone’s property if they escaped. This is how the concept of bird banding was born.

Science adopts bird banding

In the early part of the 1900s, a number of scientists started banding programs independently to learn about bird movements, particularly migration. They would put a number and their address on the band with a request to return the band if found (almost inevitably on a dead bird).

This resulted in a hodgepodge of systems. In North America, these were fairly quickly organized into a single system with a single clearing house, where all band info was sent when found.

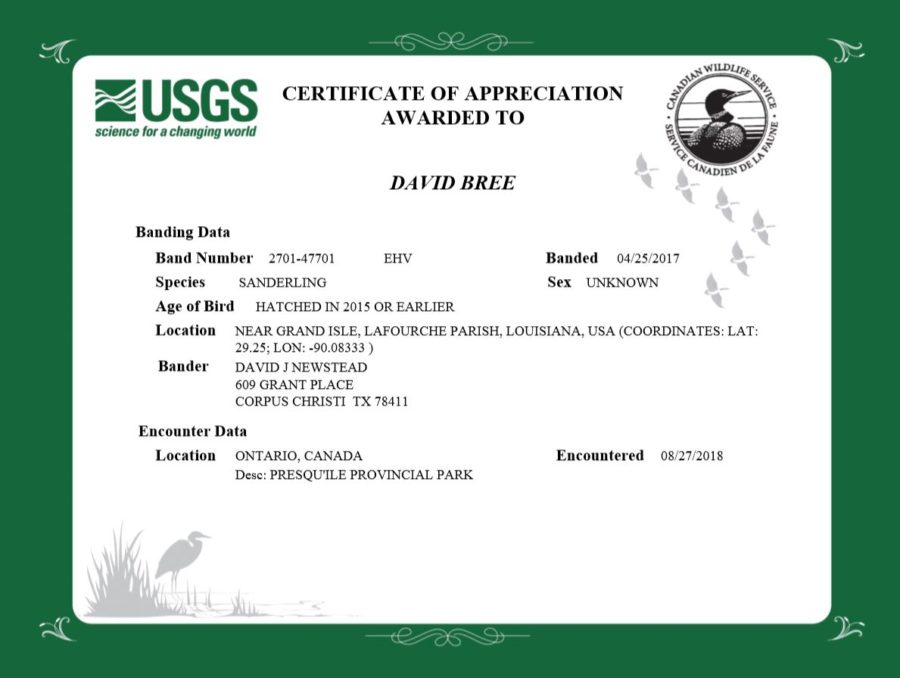

To encourage participation, the finder was sent a certificate of appreciation, letting them know where their bird had been banded. This system has been administered by the U.S. Geological Survey for decades now.

Technology and practices always improving

Band returns are traditionally less than 1%. This doesn’t sound very efficient, but with millions of bands being used for more than 100 years, patterns of bird movement have built up, giving us the knowledge we have today.

Like many other things, the rate of knowledge accumulation has increased exponentially in the last 20 years and is still building.

Electronic tags and satellite trackers can now be used on birds and there are many websites that show movements of individual birds.

Keep an eye out for bands!

Despite the new tools, old fashioned bands — through the participation of ordinary citizens — continue to be valuable.

With the increase in birdwatchers with spotting scopes and telephoto digital cameras, more bird tags can be read without capturing the bird or finding it dead.

Scientists have also made things easier for some projects by placing larger coloured bands on the birds, which are much easier to read at a distance.

The birds that come to Presqu’ile

It is always exciting to see birds and find out where else they have been. This August, we saw a Sanderling at the park with a green leg tag saying “EHV.”

Turns out, it was banded in Louisiana in April, 2017. Then it would have been heading to the arctic to nest. Now, two summers later, it was heading back south.

Results like this help scientists piece together the migration movements of shorebirds. Also seen this year was a Caspian Tern with a white tag, also in August. Turns out, it was banded as a chick in a nest on our own Gull Island back in July, 2008.

This kind of information shows us ages of birds and how some species have site loyalty, coming back every year to the same place to nest.

The wind riders

Shorebirds are great wind riders. Other banded birds seen at Presqu’ile include:

- a Semipalmated Sandpiper in June of 2011, banded in French Guiana in January, 2009

- a Ruddy Turnstone in June of 2013, banded in Brazil earlier that year

For all the birders

You can help track the wind and the birds that ride it.

Many of our parks are great places to search out birds and if you can see a number on a metal band or a plastic tag, that information can be reported to the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center Bird Banding Laboratory.

If they can find a match, you will get an electronic certificate by email letting you know where your bird was banded. This can take seconds or months, so patience is imperative!