Today’s post comes from Sonje Bols, a former naturalist at Grundy Lake Provincial Park.

Part of a park naturalist’s job is to familiarize themselves with the natural and cultural wonders of their park through exploration.

Whether it’s hanging out at bogs to catch and identify dragonflies, checking rocks for snakes, or canoeing along Indigenous canoe routes, naturalists set out to observe and explore every inch of their parks so they can bring that knowledge and experience to park visitors and managers.

With that in mind, Grundy Lake Provincial Park‘s naturalist staff made a plan to embark on a canoe trip along the Pakeshkag River in late August of 2018.

This river connects the central Pakeshkag Lake to Cantin Lake and the Pickerel River to the north. The Pickerel River joins the iconic French River, the first designated Canadian Heritage River back in 1980.

That means you can plan a canoe trip to this heritage river from Grundy Lake Provincial Park!

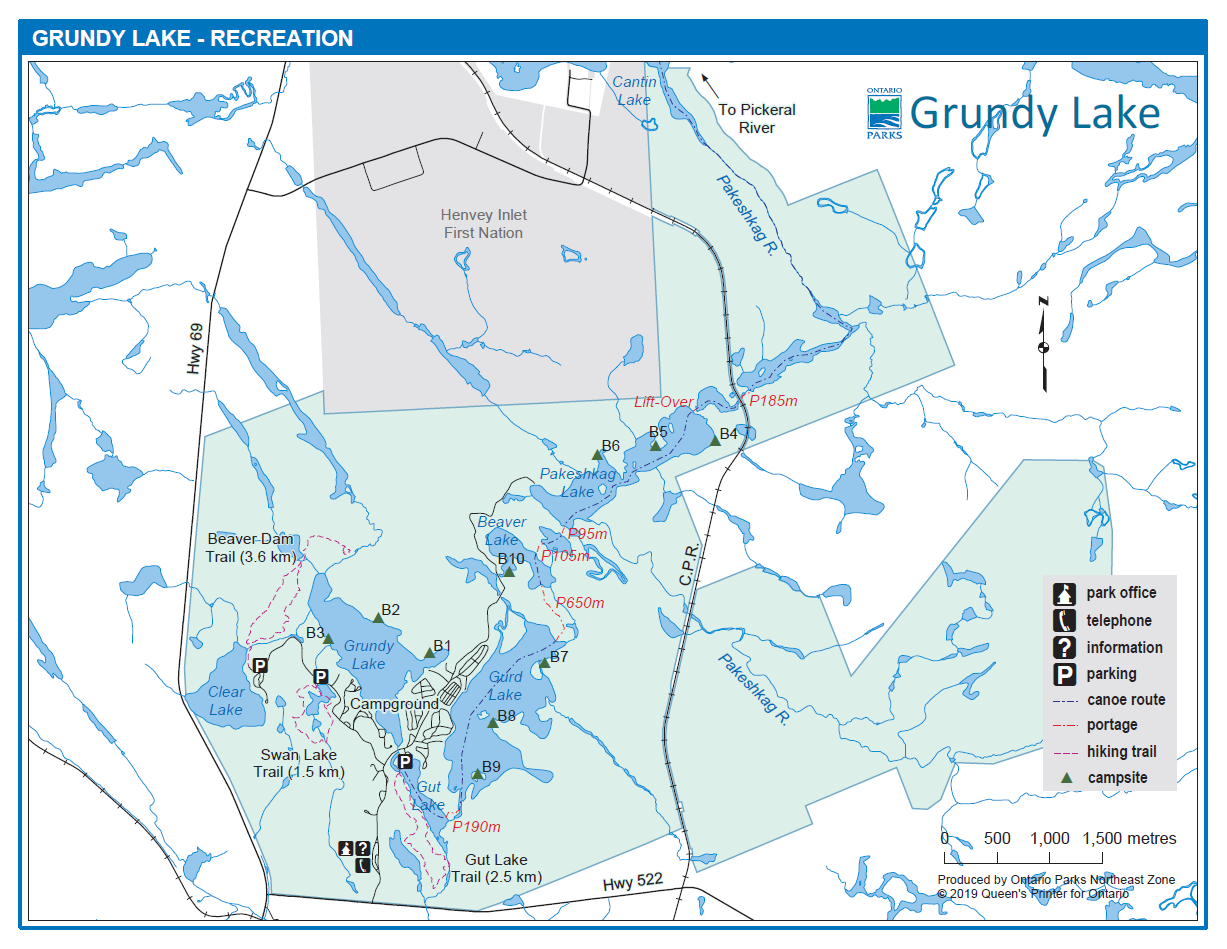

There are a few options for accessing Pakeshkag River:

- paddle Gurd Lake north through Beaver Lake and a few portages to Pakeshkag Lake

- skip the tough 650 m portage between Gurd and Beaver Lakes and portage 1.2 km along Pakeshkag Lake Trail to Beaver Lake (look for the Beaver Lake sign)

- portage the entire 2.6 km length of Pakeshkag Lake Trail to Pakeshkag Lake

Tip: a canoe caddy works well for these two latter options!

On the level

Another purpose of the trip was to see what the water level situation was.

You may remember that most of Ontario experienced a very dry summer. We were curious whether the Pakeshkag River was even navigable in a dry year! As we paddled the length of Pakeshkag Lake, we hoped we’d be able to make it all the way to the Pickerel River.

Setting out

The day began a little cool and overcast, but soon became sunny and warm. We shed our sweaters while paddling by the pine forests and the smooth, rocky shorelines of the lake.

After about an hour of paddling, we came across a “lift-over.”

Here, the route is blocked by a narrow rocky peninsula approximately 3-4 m across that you must lift your canoe over, rather than portage. The beautiful views and smooth, sloping rocks made it the perfect place for a picnic and a swim!

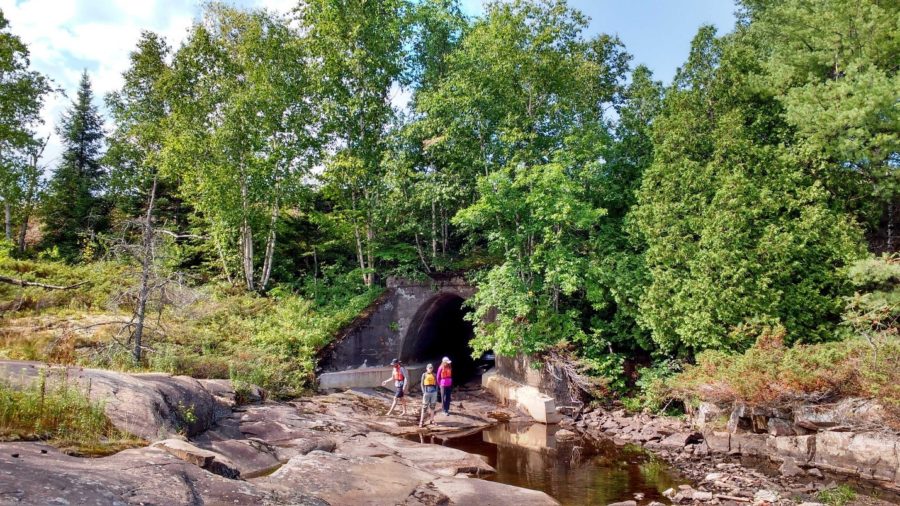

After another 15 minutes of paddling, we arrived at the 185 m portage, which also happens to cross a railway bridge.

The portage is marked to begin just before the bridge, but as water levels were very low, we opted to check out the tunnel under the bridge to see if we could carry our canoes through it. In higher water levels, this isn’t possible, and the portage is the way to go.

These low water levels gave us the opportunity to explore an area which would otherwise be hidden underwater.

We spotted Mink Frogs and Cardinal Flowers where a small waterfall normally gushes, and hopped from rock to rock, which were covered by water just a few months prior.

Under pressure

Grundy Lake is a park that has been shaped by water and ice.

Glacial ice sheets ground down the ancient Canadian Shield for thousands of years. When that ice began to melt here about 10,000 years ago, water flowing under great pressure between the ice and rock scoured and sculpted the bedrock surface.

Hollows in the bedrock now hold lakes and wetlands, which make Grundy Lake a collection of diverse habitats for plants and animals.

Carrying on

Once again, we jumped in our canoes and onto the Pakeshkag River, taking care to avoid the large patch of Poison Ivy at the end of the portage.

After 30 minutes or so of paddling across the wide river, it turned to the north and narrowed significantly.

Dramatic rocky shorelines faded away to a meandering brown river filled with waterlilies. The shore was lined first with forest, then grassy wetlands.

Travel was tricky at times, our paddles being used more for poling than paddling, but we were still able to make steady and rewarding progress along the river. We pulled our canoes over five beaver dams, the river channel becoming a little narrower and deeper each time.

A good builder

Beavers are nature’s engineers: they build canals and dams, all in an effort to control the flow of water. Beavers are almost aquatic and adapted to live in water, with webbed feet for swimming, a third clear eyelid, and waterproof fur.

These furry creatures want to build their lodge in the middle of a big pond, so their predators (wolves and bears) won’t be able to reach them. Beavers eat the twigs and branches of trees like aspen and birch, and cut down those trees using their sharp front teeth.

Water means safety for a beaver, so they build dams and flood areas to get as close to trees as possible. They store the branches under water, like a fridge, to keep them cool and preserved.

Friends to flora and fauna

We enjoyed being able to see the (otherwise underwater) entrances to a beaver lodge, and several basking Painted Turtles. When beavers build their dams, they create important habitats for plants and animals that live in water and at the water’s edge.

An Olive-sided Flycatcher swooped over us at one point, and our hearts skipped a beat when we spied a Twelve-spotted Skimmer. This distinctive dragonfly is fairly common in the area but had never before been recorded in the park!

Park staff keep records of plants and animals seen throughout the park, using iNaturalist, eBird and other nature apps.

Flycatchers and dragonflies are among the many creatures that inhabit the area between land and water, known as “riparian” habitat.

Luckily for paddlers, Grundy Lake has a wealth of these types of ecosystems.

The river eventually joined with Cantin Lake and the Pickerel River. From here, it was a windy but scenic paddle to the Pickerel River bridge along Highway 69, where our ride home to the park was waiting.

All journeys must come to an end

Overall, the trip took us six hours and was approximately 8 km there and back.

Not only were we able to successfully navigate this beautiful route (and recount the experience to inquiring park visitors), we were also able to see it in an incredibly unique condition.

We recorded dozens of wildlife records for iNaturalist, including one species new to the park! Records like this help park managers maintain ecological integrity in provincial parks.

What better way for a bunch of park naturalists to spend the day?