Today’s post is from Justin Peter, who was a Natural Heritage Education Specialist at Algonquin Provincial Park from 2006 through 2013. Now a professional travel planner, Justin is a keen local and worldwide explorer, looking for birds everywhere he ventures.

It’s tempting to say that winter’s not the best time to look at birds in our Ontario Parks. Many species have migrated south. We’re hesitant to venture into the chilly weather.

But the quieter (and leafless) atmosphere of our parks during winter provides an excellent and unique challenge for our sense of environmental awareness.

Up for the challenge?

Here’s a selection of birds (and bird signs) you can look for this winter:

Grouse that teeter

Ontario has three species of grouse. During the summer, you’d typically encounter these chicken-like birds feeding on the ground. In the winter, however, grouse are commonly found in the treetops. Their ability to feed and balance, even amongst the finest branches, belies their rotund appearance!

The Ruffed Grouse is the most cosmopolitan grouse species, and you stand an especially good chance of encountering one (or even a number of them) in a forest with good numbers of mature White Birch or Trembling Aspen.

Grouse will feed high up on the trees’ catkins (unopened flowers) or buds, completely undeterred by your presence.

The catch: it’s possible to miss them entirely because they can be so quiet!

If you’d like a chance to spot them, it’s a good idea to occasionally look up while walking through appropriate habitat.

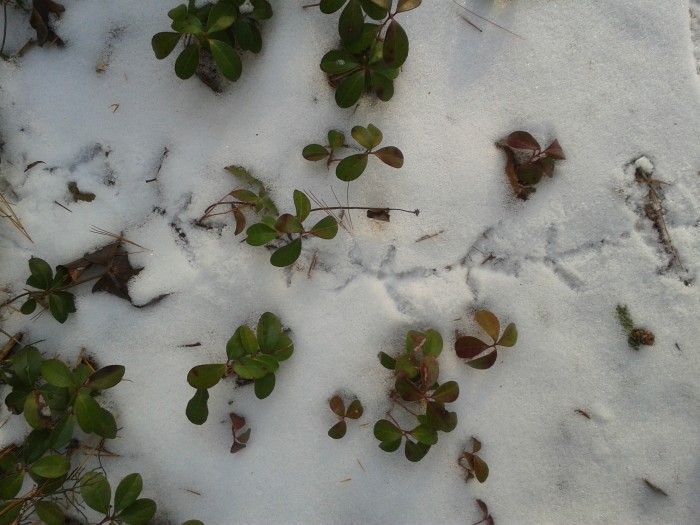

A sure-fire way to know if ruffed grouse is even in the area is to look for their trails in the snow below. Keep your eyes peeled for three toes pointing forward, each track a couple of inches long.

In areas of extensive spruce or Jack Pine trees, watch for the similarly quiet Spruce Grouse feeding on the trees’ needles up in the treetops.

A fairly unique nest

Winter is a great time to spot and study bird nests, and the used nest of the Red-eyed Vireo may be the most recognizable of all!

The tightly woven nest measures about 5 cm wide by 5 cm deep, and is typically suspended in a horizontal “Y” fork of a young tree, sometimes as low as three feet above the ground.

The nest usually has several strips of White Birch bark or similar pale material sewn into the exterior of the cup.

You’ll often find the nest immediately beside a trail or along the edge of a forest. A similarly constructed nest found in a conifer may belong to the Red-eyed Vireo’s cousin, the Blue-headed Vireo.

Don’t linger waiting for the nest-makers to return, though. Red-eyed Vireos are long gone, spending the winter months in South America.

The loud and flashy woodpecker

With its conspicuous red crest, the crow-sized Pileated Woodpecker is easily the most spectacular and unmistakable of Ontario’s woodpecker species. Mated pairs defend year-round territories in mature hardwood and mixed forest.

While their territories are large, they often betray their presence at great distance by their lively and far-carrying advertising call: yak-yak-yak-yak-yak-yak-yak. They call with greater frequency as spring approaches and may be more audible later in the day.

Even if you don’t hear one, woodpeckers betray their presence by the tell-tale rectangular feeding cavities that they bore into dead or living trees infested with carpenter ants. Some of these cavities can be a couple metres long!

Fresh chips on the snow below will tell you that the work is recent. A bird may return to a tree several times, so even if you don’t see one on a recently bored tree upon your visit, it may be possible to see it later at the same spot.

The Pileated Woodpecker is fairly confiding and may allow you to watch it at a distance of a few metres. If you see one at work and have any doubts about your ability to approach quietly and gently, enjoy the view of flying wood chips from where you stand.

The Brown-capped Chickadee

Almost everyone is familiar with the Black-capped Chickadee, the confiding little bird that often approaches us for free handouts, uttering the clear and familiar chick-a-dee-dee-dee call.

But have you ever heard or seen the brown-capped version?

It’s the Boreal Chickadee, the Black-capped Chickadee’s more reclusive cousin.

Sticking fairly closely to spruce-dominated habitats, it’s not one you’re likely to see in more southern parks, but it is a possible sighting in and north of Algonquin Provincial Park. The Boreal Chickadee utters a distinctive nasal tseek-a-day-day call that may be the first way you detect its presence.

If you’re in a spruce-dominated forest and come across a flock of Black-capped Chickadees, it’s worth looking at each bird in case there’s a silent Boreal Chickadee among them. Getting a good view of one may be challenge, but you’ll enjoy the lovely varied brown and grey tones of this unassuming bird.

Are you ready for the Winter Bird Challenge?

Seriously consider using birding-grade binoculars at 8×42 magnification.

Worn with a special and inexpensive binocular harness, your “bins” make a great addition for a ski or snowshoe excursion or a walk.